Eco: Majka Burhardt Leads Climb to Save the Planet

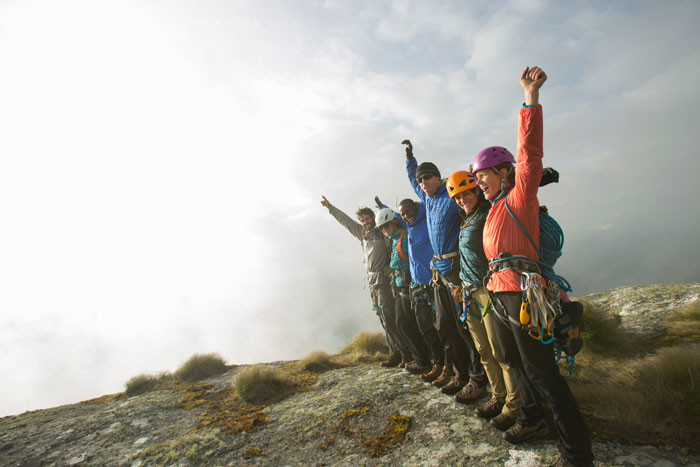

Six years, three expeditions later: Professional climber and author Majka Burhardt’s newest sustainability project and documentary debuted on the big screen in Seattle, Washington, on March 8. Namuli documents Burhardt and her team’s discovery of Mount Namuli, a 7,936-foot granite inselberg in northern Mozambique. An island mountain that first sparked her curiosity with a photo in 2010. A world-renowned social entrepreneur, in May 2014, she led an 18-member team of climbers, biologists and conservation workers to explore this threatened habitat.

Alongside professional rock climber Kate Rutherford, the duo established the first technical climbing route on Mount Namuli: Majka and Kate’s Science Project (5.10, IV, 12 pitches). Without those bolts, scientific research on the vertical face would not be possible. The climb linked together crucial habitats for researchers including a hanging pocket forest at 5,250 feet, a vegetated chimney, and sedge communities near the summit. The crew’s discoveries included two new species—a snake and a frog, plus 11 herpetofauna—and the world’s southernmost sighting of a Caecilian. So far.

But Burhardt’s overarching goal? To spearhead a community-rooted conservation model. Namuli, the project, is Burhardt’s flagship initiative of Legado, an organization that she founded in 2010. Legado’s mission is to catalyze the protection of precious ecosystems through methods that support peoples’ livelihood. Encircling Namuli is a population of more than 10,000 people—primarily subsistence farmers—that rely on the mountain for its fresh water, remaining forest and rich, arable soils.

Brimming with undiscovered species, Mount Namuli is positioned in one of the world’s designated 35 biodiversity hotspots. The monolith stands in the Eastern Afromontane region: a discontinuous chain of four mountains ranges that stretch from Saudi Arabia to Mozambique. Lavish areas, hotspots support human livelihood with natural resources such as clean water and raw materials—and are also sieged by threats. Each biodiversity hotspot has lost at least 70 percent of its original natural vegetation. Close to one-third of the 11,000 species in the Eastern Afromontane region are endemic. And hotspots now cover only 2.3 percent of the planet, collectively, according to the Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund (CEPF) 2014 Annual Report.

With no official path of sustainability, Mount Namuli’s ecosystem remains at risk.

We caught up with Majka Burhardt to find out more about Namuli and Legado. This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Majka Burhardt shows South African entomologist Caswell Munyai cliffside ecology access, photo by James Q Martin.

Why is Mount Namuli’s geology, and subsequent ecosystem, so significant?

Namuli is an inselberg: an island mountain. One of the unique features of inselbergs—and of Namuli in particular—is that species have evolved with unique characteristics on the mountain, because of its isolation. My academic background is in Anthropology for my B.A. and Fiction for an MFA. I am not a biologist. When I explain Namuli, I do it as such:

Millions and millions of years ago, all of these mountains were linked by rainforest, which allowed species to move back and forth between them. When the rainforest disappeared, species became isolated and evolved with separate, unique characteristics. That’s the definition of endemism, and the reason why scientists get so excited about studying Namuli and other inselbergs.

What needs to happen for Mount Namuli to be protected from degredation?

Right now, Namuli has no protection status. Equal in importance: it lacks medical, agricultural and educational support. Legado is doing the groundwork to understand the needs and priorities of the local people, and to gauge their level of interest in community conservation and improved resource governance. All of our work is done to support the communities that live on Namuli. They should have a range of options, so that they can determine how to move forward to protect Namuli.

Mount Namuli, photo by Rob Frost.

What is at risk if Mount Namuli is not formally protected?

Namuli’s biodiversity offers a range of ecosystem services to the local people who live on the mountain. Those services will disappear if the unsustainable resource use and agricultural practices continue. Therefore, what is at risk is everything Namuli provides—water, rainforests, soil, animals, trees, etc. In order to support a change of use pattern, any conservation work has to be paired with development to afford viable alternatives to the local people.

What are Legado’s ongoing efforts on Mount Namuli?

Our field team is getting ready to head back into Namuli post-rainy season—right now—and will be there from May to December. We will work to develop the natural resource use and socioeconomic baselines for the communities that encircle Namuli. Conduct permagardening training for local farmers, and work to build a group of local decision makers and stakeholders that will chart Namuli’s future.

It’s especially important to understand is that this work is in an early stage. Much of the information that’s needed about the people living on Namuli—such as what they are doing with their resources and how they are allocating their land—has not been compiled, yet. Our Mozambican-based field team will be the first group to survey the inhabitants of the whole mountain. That data—and the locals’ answers—will inform the next steps.

Majka Burhardt climbing Mount Namuli, photo by Rob Frost.

How has the Mozambique expedition catalyzed other initiatives?

On my reconnaissance expedition to Namuli, in 2011, I wanted to make sure that my idea—to combine science, climbing, and conservation—was viable. I could not have dreamt that we’d be doing the work that Legado is doing now. I did not imagine that we’d have an entire education platform that advances leaders in conservation and development (our Fellows program), or that we’d be talking about virtual reality media to share the Namuli story. It’s been an extraordinary journey.

Where will Legado go next?

We do plan on scaling what we’re doing on Namuli to other areas—after we’ve seen, tested, and vetted what works. In the meantime, one of the things that I enjoy most about our work is that we incorporate a lot of people with broad skill sets and backgrounds. Those people are already bringing principles and ideas into other areas, accordingly. That means, while Legado is focused on Namuli and its Fellows program, the impact is spreading.

Majka Burhardt, photo by Fredrik Clement.

Majka Burdhardt is a filmmaker, author, Founder of Additive Adventure and has spent more than 18 years leading international ventures as a social entrepreneur. Learn more at www.majkaburhardt.com and www.legadoinitiative.org.

LET'S GET SOCIAL